Have you read Hurricane Season by Brit Bennett? Or perhaps, Nightshade Market by Min Jin Lee? Actually, those are trick questions- I know you haven’t read either because neither of these novels exist, they were instead “hallucinated” by AI and then published as part of a reading list in the Chicago Sun-Times. I’ve been thinking a lot about reading lists recently, or more broadly, the authority and curation that such lists wield and what that communicates about what we value, legitimate and canonise. And remember.

Hoisting the banners

Soraya Murray’s The Triumphal Procession has been stalking me ever since I read it. Murray poses, “in the writing of histories, violent erasures go on in the process of constructing the very ground upon which the telling of subsequent historical versions becomes possible.” She characterises historicism as “a triumphal procession of not only present rulers, but all past rulers, holding aloft their venerated cultural treasures, while trampling beneath them those they have bested.”

In my mind, there is no clearer example of the triumphal procession of video games than the “Top Video Games of All Time” lists that proliferate across games media. These are a form of reading list, or perhaps “playing list” of what critics consider to be canonical examples of the medium. You could write a book just on the social, cultural and historical implications of how these lists have been written and compiled over time (and indeed, form a meta list of lists). However, for the sake of this piece I looked at a few recent ones, and found that both Rolling Stone and IGN have published lists in the last year that gave Breath of the Wild the moniker of Best Video Game Of All Time. Besides that, you get a lot of the usual suspects popping up; Minecraft, Red Dead Redemption 2, The Last of Us.

It’s not that these lists are inherently bad, or that their writers are claiming them to be definitive. I suspect that their controversial nature is one of the main reasons they get written at all, they appeal to algorithmic outrage. I can’t even argue that they’re wrong, because any list is just as wrong as another according to subjective opinion and metrics. However, the patterns in what gets covered does suggest that there is some kind of popular video game canon that exists. The existence of any canon, then, implies a non-canon. We see the same banners passing by in the triumphal procession, but what doesn’t get celebrated? And why?

Banging the drum

The triumphal procession doesn’t just apply to games media, it applies to academia as well. I’ve been turning the question of what games get covered by the academy, and why, over and over in my head like a fidget toy. Here’s the thing: arguably my most successful research article is the one I wrote at the start of my PhD about Elden Ring. It’s led to lots of opportunities for me, including more writing about Elden Ring. I don’t want to dismiss the strength of that work, but I can’t help but think that a big part of the reason it’s the research that people remember is because they also associate it with a popular video game.

When I did an interview study in the much, much more obscure Wurm Online, a senior academic asked me why I hadn’t done it in Skyrim instead. The main rationale for this, as far as I could tell, was that Skyrim is a much more popular and well-known game. As much as I find this frustrating, I have to concede that there are practical reasons for why scholars might study a popular game. For one thing, if you’re interested in community events and dynamics on a large scale, for example, then a multiplayer game with a robust player base is kind of crucial. Or let’s say you want to study meme culture and video games, it makes sense to look at a game with a burgeoning online fandom. There’s also an argument to be made that using a better known game as an example makes your work more accessible to wider audiences. Minecraft might be good as a case study because even people who don’t regularly play games likely have some frame of reference for what it is. Also, it’s easy to slip into snobbery at “mainstream” games, but just because something is obscure doesn’t make it more interesting.

On the other hand, Wurm Online is both obscure and interesting. I wanted to study it because it has a core dedicated player base of about 100 people that continue to tend to it – the game has a mechanic where structures and objects will degrade over time unless players actively maintain them. Wurm launched in the heyday of MMOs in 2006, and its oldest server has been online since 2009. It was here that I did my go-along studies, focusing on a tunnel that would have taken literally thousands of hours to create, that has been designated as a heritage site by the in-game community. Exploring abandoned MMOs has become a popular YouTube video genre, but Wurm is a great example of an online game that is neither abandoned nor thriving, existing somewhere in between. Such a game can easily slip through the cracks, not toeing the line of the procession.

Keeping time

I suppose what I’m really advocating for, is not a complete cessation of the video game triumphal procession, but more an interrogation of why it exists and an honest account of how we’re influenced by it in our work. Also, it’s good to reflect how it manifests in different academic communities. Sure, you would expect that Pokémon Go got a lot of coverage in the spatial and digital humanities after its boom in 2016, but did you know that the academic procedural generation community endlessly publishes papers on generating levels for Super Mario Bros? It’s kind of an in-joke at this point.

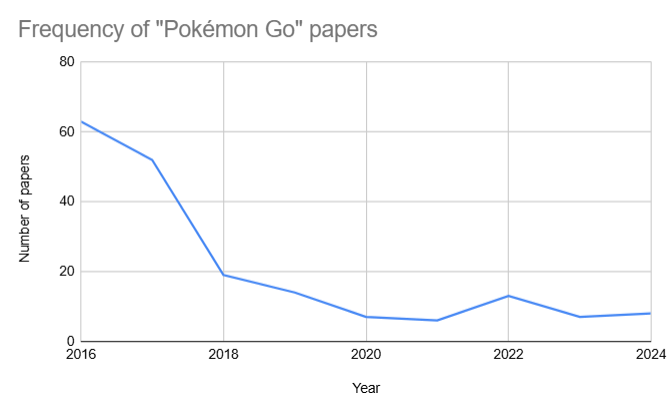

I was curious about the frequency of papers published about specific games over time, so I did a very cursory investigation on Google scholar. I searched for papers with the exact phrase “Pokémon Go” and “Super Mario Bros” in the title and filtered by year. I should stress that this is not a rigorous analysis (there may have been duplications I missed, for example) or the best methodology, but purely for quick illustrative purposes here are the two graphs I produced as a result:

You can see how papers about Pokémon Go follow the 2016 boom and then quickly drop off. In contrast, papers about Super Mario Bros only really started to appear in the late 2000s and then to really gain traction in the 2010s as the game became a testing bed for PCG and AI research. I love these two examples because one follows wider commercial trends, while the other is the result of a smaller, stranger triumphal procession that most people can’t even see.

The end of the procession?

After that detour, let’s circle back to the fake reading list. You know, the AI one.

I’ve recently been enjoying Janelle Rebel’s absolutely wonderful Bibliographic Performances & Surrogate Readings, which is all about the poetics of bibliographies. In an early chapter, she reflects on the apparent irrelevance of hand-curated bibliographies with the advent of instant Google searches. However:

“Subject bibliographies wrench resources out of search-driven systems and into the realm of spirited recommendations, troubling arrangements of resources, challenging canonical norms, countering algorithmic suggestion loops, and constituting new thought models.”

I feel like fake AI reading lists are the ultimate result of a triumphal procession without context or scrutiny: “well, if there are a few big names on there, it’s probably legit, right?” A lack of curiosity, an inability to look forward or understand the route taken, will lead the triumphal procession off a cliff.

Rebel’s writing on bibliographies gives me hope, though. What about the poetics of ludographies, informed by critics, developers, academics, fans, and more? What would it mean to take the tune of the video game triumphal procession, but listen to it alongside personal recommendations of bootlegs, fan works and academic provocations?

I don’t know where that road leads, but I sure as hell want to find out.