Now the dust has settled on GDC 2025, enough time has passed that I can consider it archaeology and write about it (I jest-anything anytime can be studied archaeologically, if you have the inclination). Anyway, last month I went to GDC in-person for the first time. Younès Rabii and I did a GDC talk on the ethics of game AI back in 2022, but we did it remotely due to the ongoing risk of COVID-19, so it was nice to finally get to experience the event first-hand.

Speaking of risks, it was especially risky to attend GDC this year. The event is hyper inaccessible as it is due to its location, costs and the predatory behaviour of certain game devs. This time the threat of detainment was added to the roster. It seemed like everyday leading up to the trip I heard another story of a tourist being detained under the Trump regime; I was genuinely scared and seriously debated not going. In the end, I did make the trip. Was it worth it? No. And yes.

The state of the industry, or the industry as state

Overall, I don’t think I can easily justify such a costly trip (in more ways than one) across the pond, even if I didn’t pay for it (my PhD programme did). Also, GDC as a spectacle was at times pretty alienating and overwhelming. It seems like everyone has their own meta-game for what they want to get out of the conference, and this often had me question if I was doing “the right thing” in making the most out of the experience.

I’ve also seen a lot of people discussing that attendance numbers are down and the future of GDC, at least in its current form, may be in doubt. Of course, I’ve never gone before so I have nothing to compare it to. For sure though, I think seeing GDC as the ultimate showcase for the state of the games industry is misleading at best. As the aforementioned risks would indicate, this is a table where only a select few get a seat, let alone a nice slice of the pie.

Chasing waterfalls

So what was I doing at GDC? Talking. I met and talked to a lot of people I’d only met online, and that was wonderful. As I had heard before attending, the heart of the event isn’t on any stage of the Moscone Centre, but in the park nearby, Yerba Buena. There, people seemed to gather often in spite of GDC; they didn’t have badges with access to the event but wanted to catch up with friends who they knew would be in San Francisco. This is the thing, GDC operates a lot on FOMO. Everyone goes because everyone goes.

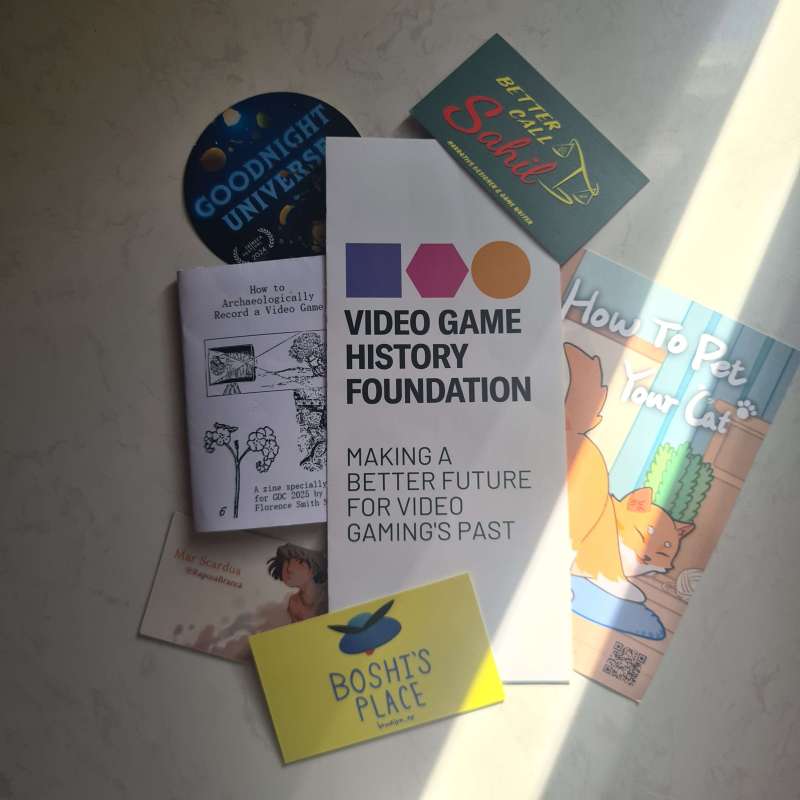

I feel like everyone should have a favourite spot in Yerba Buena, and mine was the waterfall. I kept turning up there like a bad penny (luckily no one threw me in for good luck) in order to hand out zines. I thought it made sense because, you know, cool stuff is always hidden behind waterfalls in games. I later discovered that the waterfall is actually a memorial to Martin Luther King, which makes me love it even more.

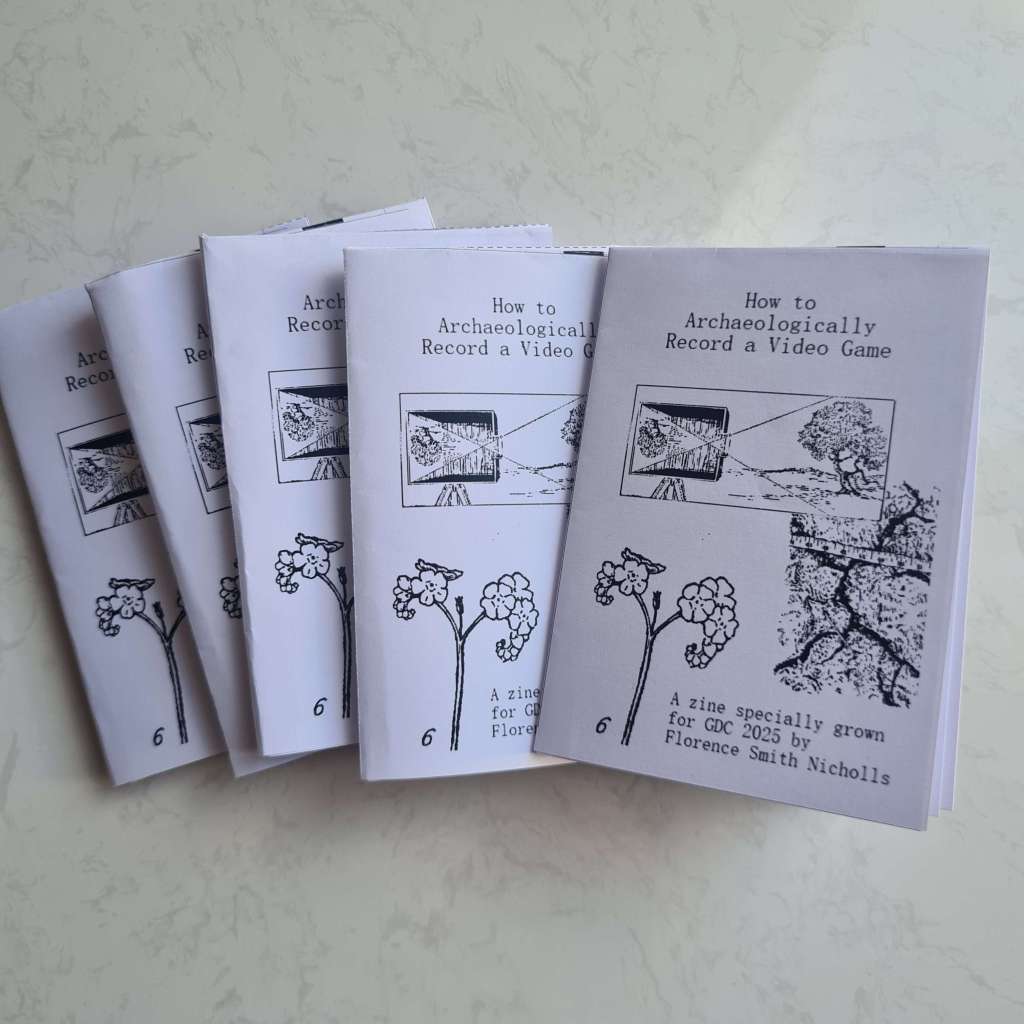

I made the zine “How to Archaeologically Record a Video Game” specially for GDC as a way to, quite literally, fold my research into an accessible form. Making it was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made regarding how I disseminate my work. It turns out zines are both a gift to share with others, and a talisman against social anxiety. I have Kate Compton to thank for inspiring me to make a zine about my research.

One of my highlights from GDC was giving a zine to be archived by the Videogame History Foundation. As I handed it over to librarian Phil Salvador, he said it would be kept beside Nathalie Lawhead’s zines, which makes for a really interesting assemblage as Nathalie created the tool I used to make my own!

How to Create a Video Game Archaeologist

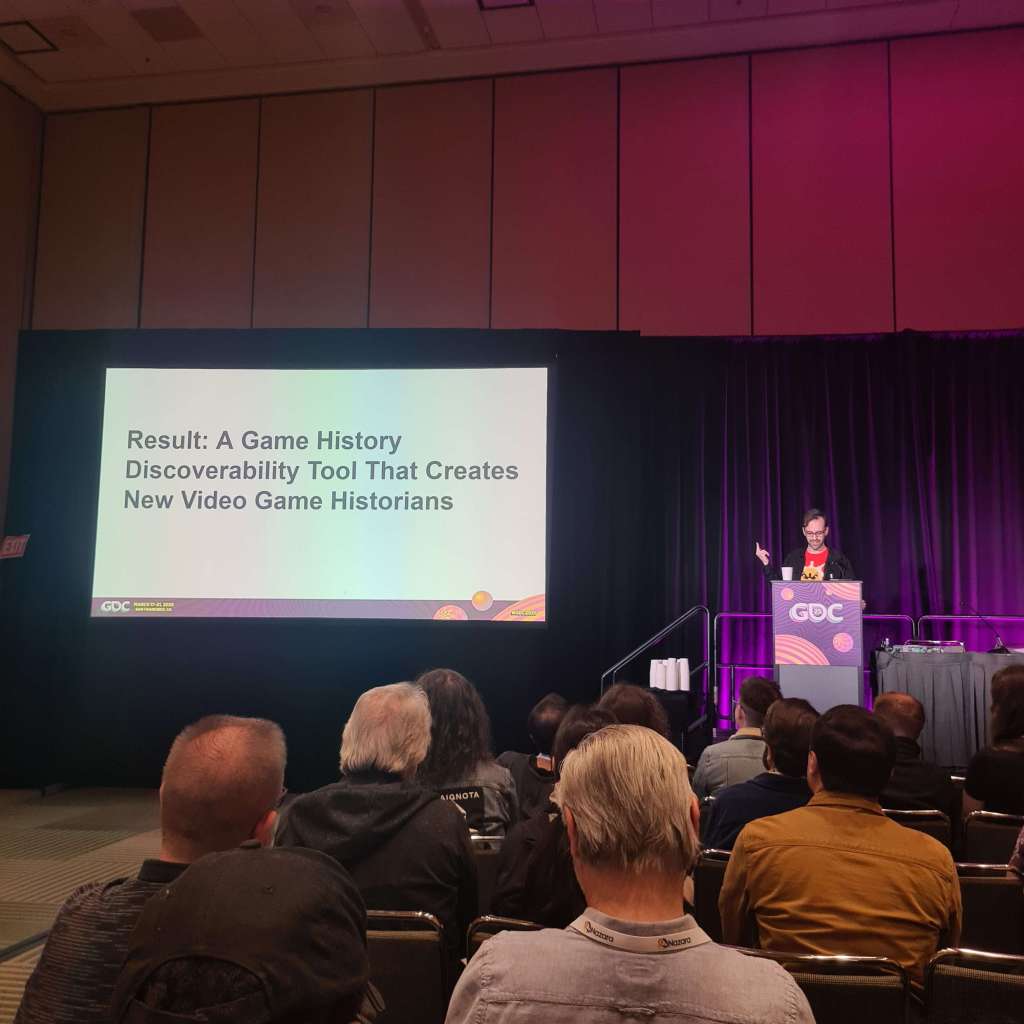

Speaking of the Video Game History Foundation, possibly my favourite talk was given by their founder Frank Cifaldi. He presented various stories about acquisitions that the foundation has made, and their new digital archive. I’ve been thinking about this slide in particular ever since I saw it several weeks ago:

I’ve often thought the benchmark for me of what makes a truly transformative piece of art is its ability to inspire me to make something myself. I’ve had this experience with games like Disco Elysium, Pentiment and 1000xRESIST. This is why the idea of producing an archival tool that creates video game historians is so compelling to me. And it got me thinking, how do I create more video game archaeologists?

For what it’s worth, archaeology came up a surprising amount at GDC. In their talk “Built in Layers: (Re)Creating History with the Narrative System in ‘Civilization VII‘” the Firaxis team discussed how they took an archaeological approach to the narrative design of the game, having players become auto-archaeologists of their own play experience. Angus Mol and Aris Politopoulos of the VALUE Foundation (of which I have worked with) presented their perspective on designing “knowledge-driven” games about the past, rather than focusing on accuracy. Finally, in the “What’s New in Game History: 2025” panel, video game historian Laine Nooney mentioned the work of two video game archaeologists, Katie Biittner and John Aycock.

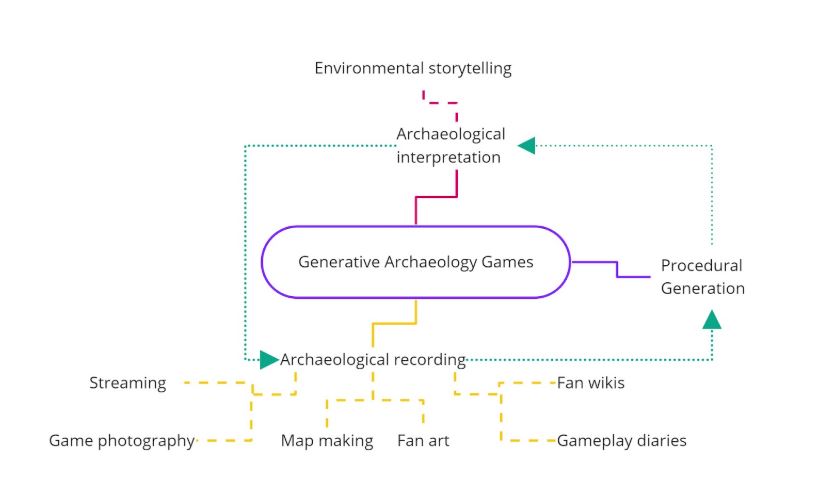

My hope is that the value of archaeological approaches to video games from a design perspective will continue to be explored among all kinds of practitioners. Back in 2022 at GDC, I debuted my idea of “generative archaeology games” that compel players to interpret their fictions and to use different recording methods like map-making and photography to preserve those gameplay experiences. I moved away from the term because I feared people associated it with generative AI, but my goal remains the same: to create more video game archaeologists.

This month, I’ll be presenting my work on archaeological gameworld affordances at CHI in Yokohama, which builds on this core idea that players are essentially role-playing as archaeologists when they interpret environmental storytelling. Maybe the question isn’t so much what’s behind the waterfall, but why something is there in the first place.

As it turns out, maybe we’ve all always been video game archaeologists.