Back in January 2023, I ran an online study in which I got participants to play a game about a ruined village and tell me what they thought happened to it. That game was Nothing Beside Remains, a 2D top-down ASCII vignette co-developed with my supervisor Mike Cook. The game procedurally generates the village – depending on how the simulation of its ruination runs, you’ll get different material culture.

It’s sort of folk knowledge at this point that players derive meaning from environmental storytelling in games, but there hasn’t been much empirical study of how and on what basis they form those interpretations. I had a strong hunch that, as a discipline that specialises in interpreting human material culture, archaeology could provide some insight into the mechanisms behind this process.

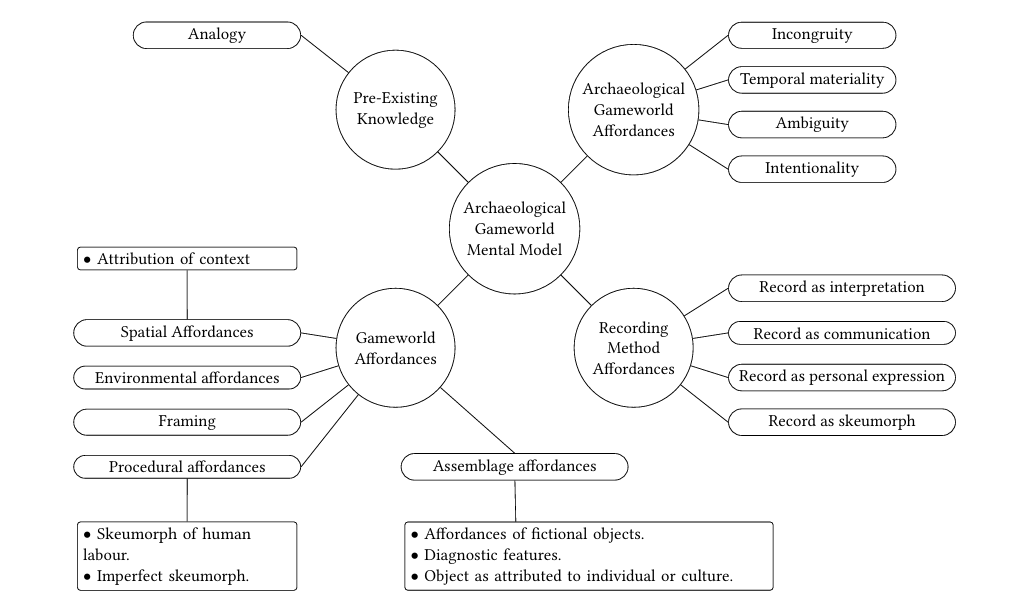

I analysed over two hundred participant survey responses. This involved what is referred to as a “grounded theory” analysis – I went through the responses line by line and assigned them “codes,” words or phrases associated with the written answers. The point of this methodology is to form a theory that is “grounded” in the data. Many hours and over 400 codes later, I came up with the theory of the archaeological gameworld mental model.

Theatre of the Mind

“Almost all of the experience was mental, taking in the objects I saw and forming my own picture of the village and what could have happened.” (Participant 167)

Several participants referred to their experience of Nothing Beside Remains, and their interpretations, being constructed through their own internal mental model. A mental model is an internal conceptualisation of how something works. My theory is that players form mental models of a fictional game world and the system that underlies it.

You can see a diagram of the archaeological mental model and its subcategories below. I’m not going to go into these in detail (please do read the full paper if you’d like to know more), but to briefly summarise; pre-existing knowledge informs the mental model, gameworld affordances (such as level design, for example) constrain the mental model, archaeological gameworld affordances inspire elaboration on the mental model, while recording method affordances scaffold the mental model. If that all seems a bit abstract, well, let me demonstrate by applying the model to the recent puzzle sensation, Blue Prince.

Out of Place

“There was a pocketwatch in a house. There were metal objects in the village so it is possible they produced the watch too, but the other objects were simple things like bowls. The pocket watch seemed out of place. Maybe another explorer simply dropped it.” (Participant 3)

Through my grounded theory analysis, I came up with the term “archaeological gameworld affordances.” Affordances, from a design perspective, refers to the qualities of an object that users perceive as potential uses. For example, a chair affords sitting, though it may have other perceived affordances that were not intended by the designer, such as the ability to hold or store other objects. Archaeological gameworld affordances refers to qualities that invite further elaboration on the mental model, either by reinforcing or challenging existing assumptions. One of the archaeological gameworld affordances is incongruity – the identification of material culture that doesn’t fit the existing model. The example above is from a participant who discovered a pocket watch in Nothing Beside Remains, an anachronistic object that led them to the theory that perhaps there was another explorer, like them, investigating the village and dropped the item.

Blue Prince is a puzzle adventure game set in a mansion that the protagonist has inherited from his deceased uncle, though in order to secure his inheritance he must enter the elusive 46th room. This is not a matter of straightforward exploration- the mansion is represented by a grid of 45 tiles, five horizontal by nine vertical rows. Every time you enter a new room “tile,” you draft from a pool of floorplans. There are a total of 110 unique rooms in Blue Prince with different contents and clues, but as procedural generation is used to determine what rooms you draw from in your pool, you will get different combinations each time. If the player hasn’t reached room 46 by the end of the day, they must start the process all over again.

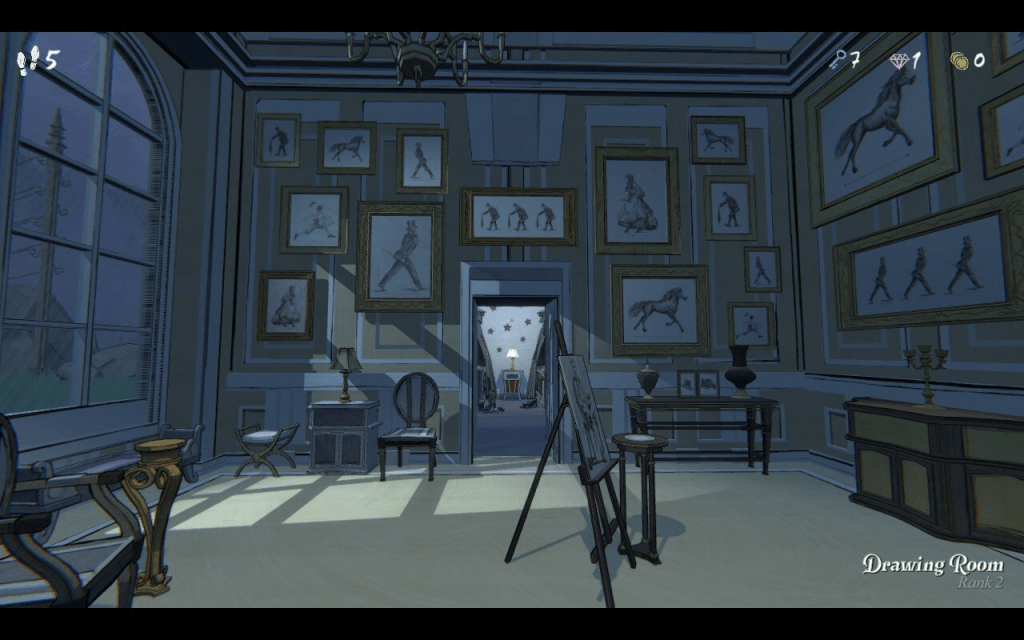

Blue Prince conveys much of its narrative, but also its puzzles, through environmental storytelling. I would argue that we can identify archaeological gameworld affordances like incongruity used to great effect in the game, and this is partly enabled by its procedural design. For example, here’s a screenshot below where you can see from the aptly named Drawing Room into the Nursery. The juxtaposition of the stars stuck on the wall in the nursery against the more austere arrangement of pictures in the Drawing Room can lead to new connections and associations being made. Sometimes the procedural drafting of rooms can literally shed new light on them- depending on a room’s placement in the house, its windows may face onto the exterior gardens, providing a new perspective and different lighting.

In the paper, I argue that “procedural affordances” of algorithmically generated content have powerful synergy with archaeological gameworld affordances, because they often result in content that is incongruous, ambiguous or uncanny. The strange texture of procedurally generated content invites speculation and interpretation. This is also why I think that Blue Prince gets better the slower you play it. Taking your time, drinking in the visual design of the rooms and their eccentricities will not only help you to solve puzzles, but it’ll make the experience of the game richer as well.

“A noteworthy adventure”

“I made a map in my notebook of the space… It definitely structured the experience. Rather than wandering it encouraged me to be systematic and observant of the space.” (Participant 201)

As mentioned earlier, one of the subcategories of the archaeological mental model is recording method affordances. In the first phase of the study, participants were asked what method they might use to record their experience of Nothing Beside Remains, whether that be screenshots, map-making or note-taking. In the follow-up study we explicitly asked participants to record their play experience and tell us what method they used and why. There were a range of different responses that demonstrated the differing affordances of recording methods, like the example above in which a participant found that making a map changed their experience of the game space.

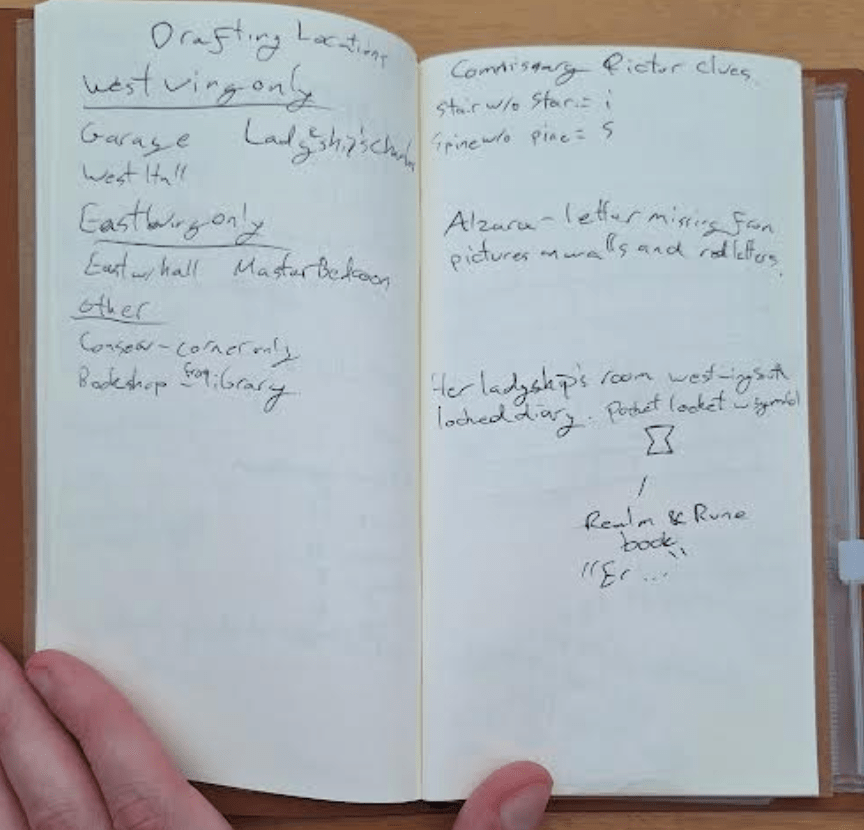

There has been discussion about how note-taking games could be a genre in their own right, but I think that Blue Prince might be the first game I’ve played that explicitly advised me to take notes. Given my interest in recording method affordances and games, I was instantly intrigued. There was a piece earlier this year in Polygon about different note-taking strategies for the game, and I also wanted to look into this further. I put out a call for photos of records or notes people had made for Blue Prince and got back a veritable archive of scribbles, spreadsheets and screenshots.

I should note here, there are some spoilers if you look too closely at any of the screenshots in the section below, but a cursory glance shouldn’t give anything away.

Record as skeuomorph

A common theme across the notes I received was a desire to record as much as possible because people didn’t know what might be relevant later. This reminded me of one of the “codes” assigned in my grounded theory analysis: the “record as skeuomorph.” A skeuomorph is an object that imitates the design features of something made in another material. A digital example of this is the floppy disc icon on a computer that evokes the connotations of the physical object.

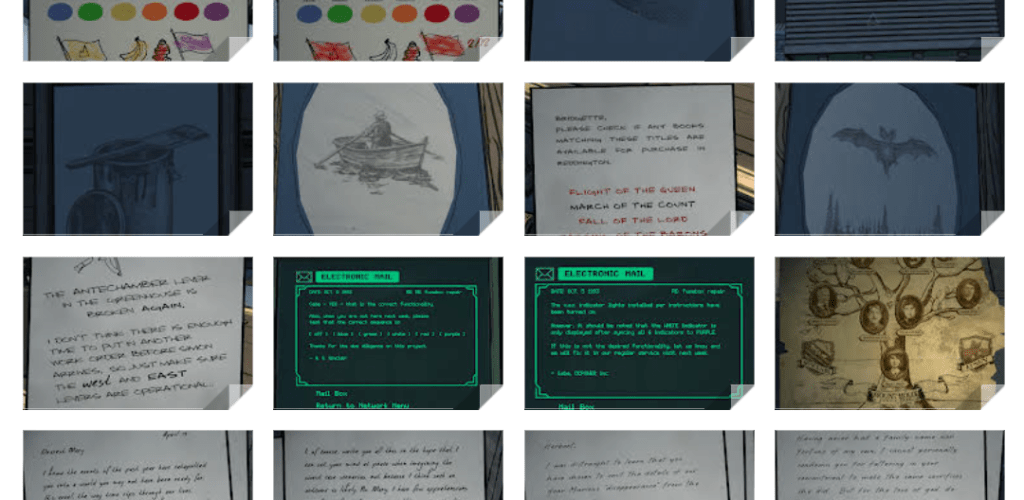

Martijn Frazer sent me his archive of 150 screenshots that he had collated over 50 hours of gameplay. The screenshot as stand-in form the gameplay experience does have a kind of skeuomorphic quality here.

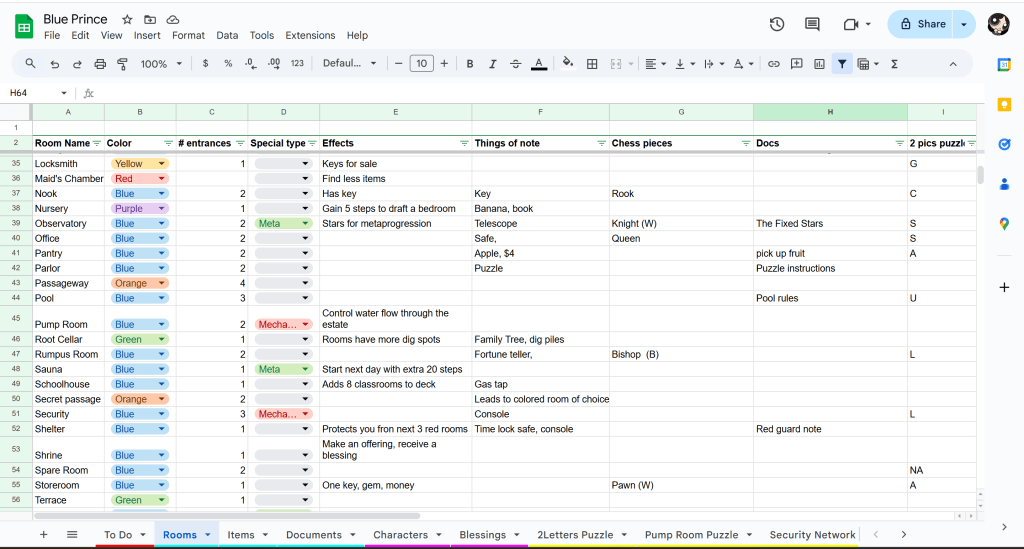

Record as interpretation

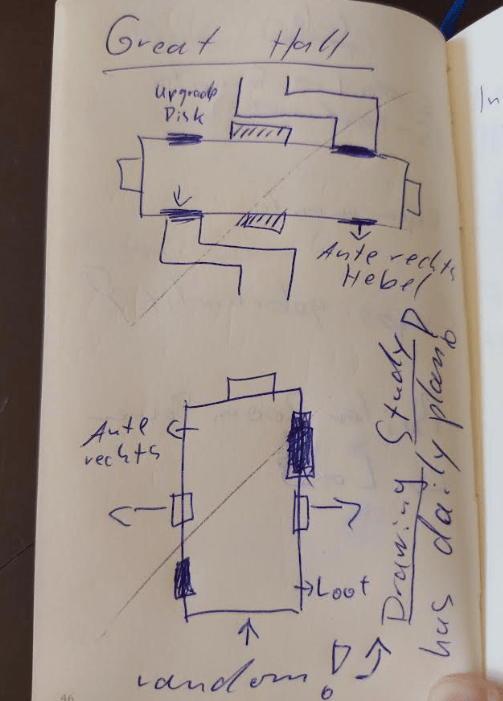

Similar to Martijn, JC Lau also recorded as much information as possible, though in her case she created a spreadsheet and carefully colour-coded the tabs based on types of information. This curation of information feels like it could fall under the category of “record as interpretation,” as the organisation of notes both facilitates and is shaped by emerging interpretations of the game. JC ended up recording which rooms she entered on each “run” and what she found in them. I also think that Pascal Wagner’s analogue note-taking process, of drawing plans and then striking them out and making amendments as his theories progressed, has parallels with this.

Record as personal expression

There are some note-taking methods that I would argue belie the personality of those who made them, even if they were not originally created with that intention. I would put myself in this category- I really enjoyed taking a screenshot of the map that the game generates at the end of each run as a way of recording the emergent designs that came out of my drafting choices.

I also really love the contrast of Errol Seymour’s Blue Prince notes with previous examples – they only used two pages of their notebook, but have been able to fit everything they needed into that limited space. Similarly, we can see flairs of Henry Stenhouse’s personality in the little details he picks up from the game, and quotes that he noted down.

First draft

The paper on archaeological gameworld mental models is just the beginning of further research I’m planning into how note-taking can enhance and shape player interpretive agency in games. Encouraging players to slow down and look away from the screen might seem counterintuitive, but I think that it’s actually a powerful way of getting people to more deeply engage with puzzles and digital space. If note-taking helps scaffold archaeological mental models when interpreting analogue archaeological remains, then it can also aid players who essentially take on the role of archaeologists when interpreting environmental storytelling. Though some of the examples above were digital, I’m particularly interested in the analogue/digital hybrid experience of taking notes by hand while playing a digital game.

I’d argue that with Blue Prince, half the fun is what happens off-screen, in your archaeological imagination.